Introduction

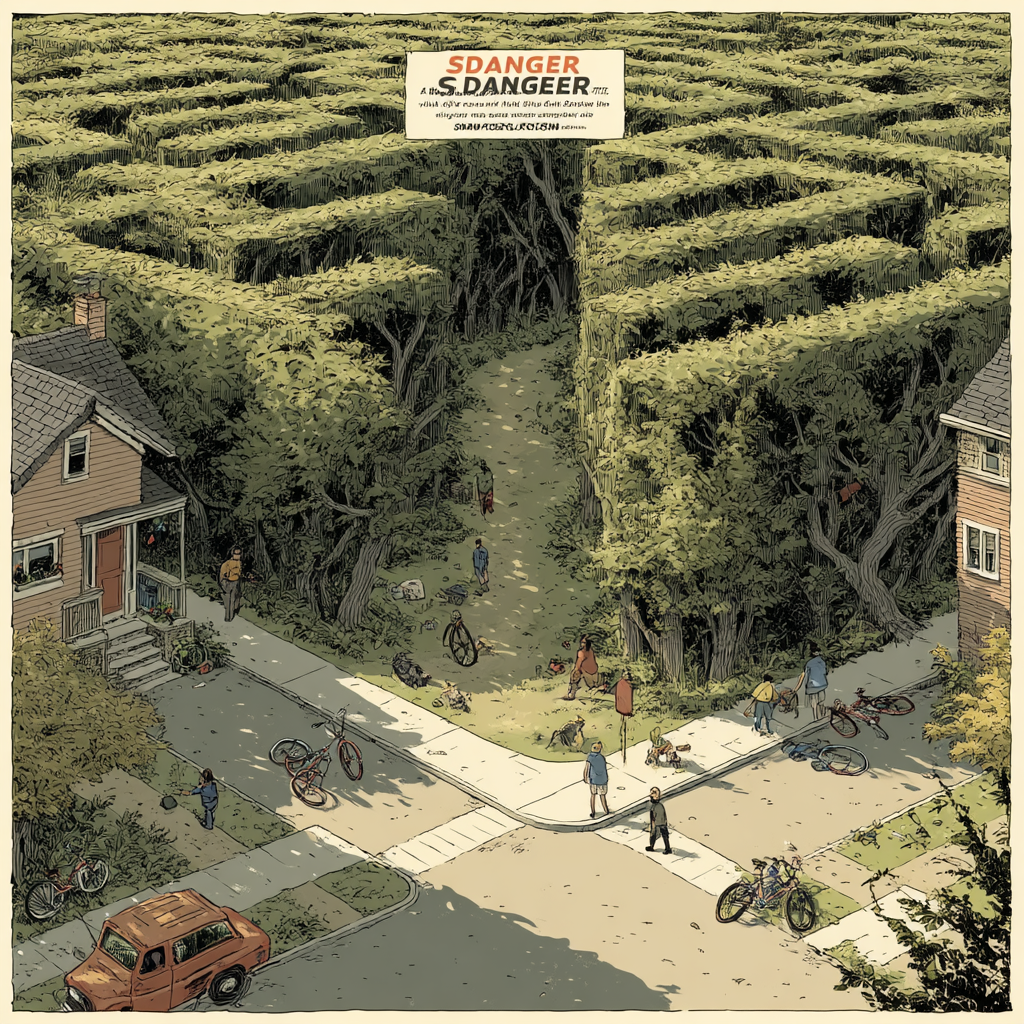

The debate over sex offender registries has again resurfaced, fueled by a recent news segment out of New Mexico. Spotlighting a military adjudication that never made it to the state’s public registry, advocates, law enforcement, the media, and distraught victims are calling for so-called “loopholes” to be closed in the name of protecting children. At first glance, the narrative is compelling: if only the registry had been more robust and public-facing, tragedy could have been averted, and children kept safe. But as the discussion unfolds—guided by podcast hosts Andy and Larry from Registry Matters—a more complicated picture emerges. Are public registries the panacea they are promised to be? What risks do they actually address, and how well? And in a world increasingly defined by digital interaction, how can parents, communities, and lawmakers foster both safety and sanity for families?

This article synthesizes the conversation, expands on its key points, and asks the tougher questions: Do registries actually prevent reoffending, or do they simply provide a comforting illusion of control? What is the real scale of “stranger danger,” and how should parents respond? And perhaps most important of all—is the intense public focus on visibility and compliance obscuring deeper societal challenges?

Understanding the Case: When the System Falls Short

The recent media segment that sparked this conversation centers on Jonathan Giacinto, an individual previously convicted via military court for child solicitation in Oklahoma. After his discharge, New Mexico law required him to register as a sex offender—but his specific adjudication only triggered law enforcement notification, not public disclosure. So, while Giacinto fulfilled his registration obligations, neighbors and potential victims had no way to search for or access his status via public databases.

When Giacinto allegedly reoffended, the case became a rallying cry for closing registry “loopholes.” Victim’s advocates, law enforcement, and local media united to argue for legislative changes that would make such offenses publicly searchable in the future. The outcry is emotional and, to many, persuasive. But Andrew and Larry urge listeners to look deeper—at not just what happened, but why, and what more comprehensive evidence reveals about registries, safety, and risk.

Section 1: The Reality of “Stranger Danger” in 21st Century Parenting

The media’s familiar advice to “teach children to avoid strangers” is comforting but increasingly at odds with data. Larry’s perspective is clear: instances of children being harmed by strangers are exceedingly rare. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, only around 100 children in the U.S.—out of a population of over 330 million—are abducted by strangers annually. In the majority of abuse cases, perpetrators are known to the victim. And yet, “stranger danger” fears have contributed to a culture of parental hyper-vigilance, limiting children’s independence and even compromising their physical and emotional health.

Key Contextual Insights:

– Noted parenting expert Lenore Skenazy, champion of “free-range kids,” emphasizes that kids are statistically safer now than ever before.

– Overestimating stranger risk can lead to a trade-off: less outdoor play, less independence, and less well-rounded development for children.

– Scarcity bias—the tendency to exaggerate rare but frightening events—may drive policy more than evidence does.

Section 2: Registry Compliance—Security Theatre or Effective Policy?

News footage of sheriff’s deputies performing “compliance checks”—knocking on registered individuals’ doors to ensure proper addresses—appeals to a sense of community vigilance. Yet, as Andy notes, the overwhelming majority of registered persons are already hyper-compliant, fearful of even minor technical violations. Rather than catching non-compliance, these checks often serve a public relations function: assuring neighbors that action is being taken, even as those knocked-upon continue to face intense stigma and barriers to reintegration.

Potential Unintended Consequences:

– Public compliance checks, often accompanied by flashing patrol lights, can mark individuals’ homes, causing neighbors to view them with suspicion or fear.

– This stigma can interfere with employment, housing, and rehabilitation—arguably making it harder for individuals to build stable, law-abiding lives.

– As Larry points out, such visible enforcement often correlates with law enforcement agencies seeking federal funding, highlighting an ironic tension between professed small-government values and operational realities.

Section 3: The Digital Age—Grooming, Parenting, and Practical Limits

A critical dimension of the Giacinto case is that the alleged predatory behavior occurred largely via digital communication, followed by the minor leaving home voluntarily after months of “grooming.” Here, Andy raises poignant questions about digital-era parenting: How realistic is it to expect parents to fully monitor their children’s online presence, especially as kids become more tech-savvy than their elders?

- Federal legislation like COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act) sets guidelines for children under 13, but actual enforcement is minimal and technology moves rapidly.

- Despite parental intent, most teens maintain some degree of unsupervised access to digital devices and social networks.

- Expert consensus (e.g., American Academy of Pediatrics) now recommends a balance between guidance and monitored autonomy, recognizing that total control is often unachievable—and possibly counterproductive.

Larry and Andy’s banter teases out a core paradox: increased digital oversight can help, but there will always be gaps, and government intervention raises additional ethical and logistical concerns.

Section 4: Public Registries—Panacea, Placebo, or Something Worse?

Should the registry have “worked” in Giacinto’s case, or would expanded visibility simply displace the problem? Studies indicate that most offenses are perpetrated by individuals not previously known to law enforcement or included in registries at all. Even in instances where offenders are registered, the ability of potential victims or families to “lookup” threats in real-time is limited—especially in the digital age, where online handles and pseudonyms mask real identities.

Research & Expert Commentary:

– Multiple studies (e.g., Levenson et al., 2011) find no significant difference in recidivism rates before and after the introduction of public registries.

– The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that just 5% or fewer of new sexual offense arrests involve individuals already on registries.

– Rather than preventing novel offenses by strangers, registries often act as a secondary notification system after-the-fact, rather than as a primary deterrent.

Section 5: The Military, Law, and “Loopholes”

Giacinto’s case also exposes jurisdictional rifts between military and civilian justice systems. While the Army can court-martial and discharge an individual for certain acts, it is only civilian law that dictates registration requirements and public visibility. In New Mexico, crimes of solicitation in digital spaces can require registration but not public disclosure—a setup the current outcry now aims to change.

Larry is skeptical that sealing every gap will deliver the promised public safety. The drive to publicize all convictions risks conflating disparate levels of severity and, in his words, pursuing a “cure-all, end-all” policy that may do more harm than good by branding individuals for life, even as empirical evidence for effectiveness remains thin.

Section 6: Recidivism, Second Chances, and the Myth of Total Prevention

Even law enforcement in the discussed news segment admitted that the vast majority of those on the registry do not reoffend. Yet, public policy is shaped by the impossible quest for absolute safety—the idea that even a single failure justifies ever-expanding registry scope.

- Recidivism data show that sexual offense reoffense rates are among the lowest of any major crime category (frequently under 10% within five years post-release).

- The pursuit of zero-risk leads to calls for increasingly punitive, never-ending monitoring, even when such measures undermine rehabilitation and societal reintegration.

Larry and Andy drive home a final, crucial point: The registry did not deter or prevent the original offense; nor, apparently, did it prevent reoffense. Calls for perfect solutions mask a harder question—should society accept that some risk will always exist? And does the ceaseless expansion of registries have diminishing returns, or create harms of its own?

Conclusion: Rethinking Registries in a Complex World

The call to “close loopholes” in sex offender registries is emotionally potent but, as this in-depth discussion reveals, policy solutions that focus on ever-expanding lists may provide only an illusion of control. Stranger perpetration is rare. Law enforcement compliance sweeps favor perception over prevention. Internet-age challenges dwarf the protective power of name-and-photo databases. Meanwhile, individuals seeking second chances may find themselves locked in cycles of stigma, unemployment, or worse.

Rather than asking how to design a “perfect registry,” it may be time for communities and policymakers to reconsider whether public registries—at least in their current form—serve their intended goals.

Actionable Takeaways:

- Reframe the Narrative Around Risk:

Parents, educators, and policymakers should ground safety messaging in data, not fear. Focus on building digital literacy, open communication, and evidence-based prevention strategies. - Reevaluate Registry Policy Goals:

Legislatures should commission impartial research into the actual efficacy of registries, focusing on whether they prevent new offenses—and at what societal cost to civil liberties and successful reintegration. - Support Families and Survivors Holistically:

Effective prevention addresses root causes—education, support for at-risk youth, and resources for survivors—rather than over-relying on registries as “silver bullets.”

Next Steps:

– For concerned citizens: Advocate for balanced laws that address genuine risk without unnecessary stigmatization.

– For parents: Emphasize building trust and digital savviness at home, rather than relying solely on external technological “safety nets.”

– For policymakers: Resist reactive lawmaking; instead, consult with experts in criminology, psychology, and child welfare before expanding registry requirements.

Key Consideration:

As Larry quipped in the podcast, perhaps the better question is not how to make the registry perfect, but whether it should even exist at all in its current form. While there are no easy answers, honest debate—rooted in evidence, empathy, and realism—offers the best hope for protecting both children and civil society.

Leave a Comment