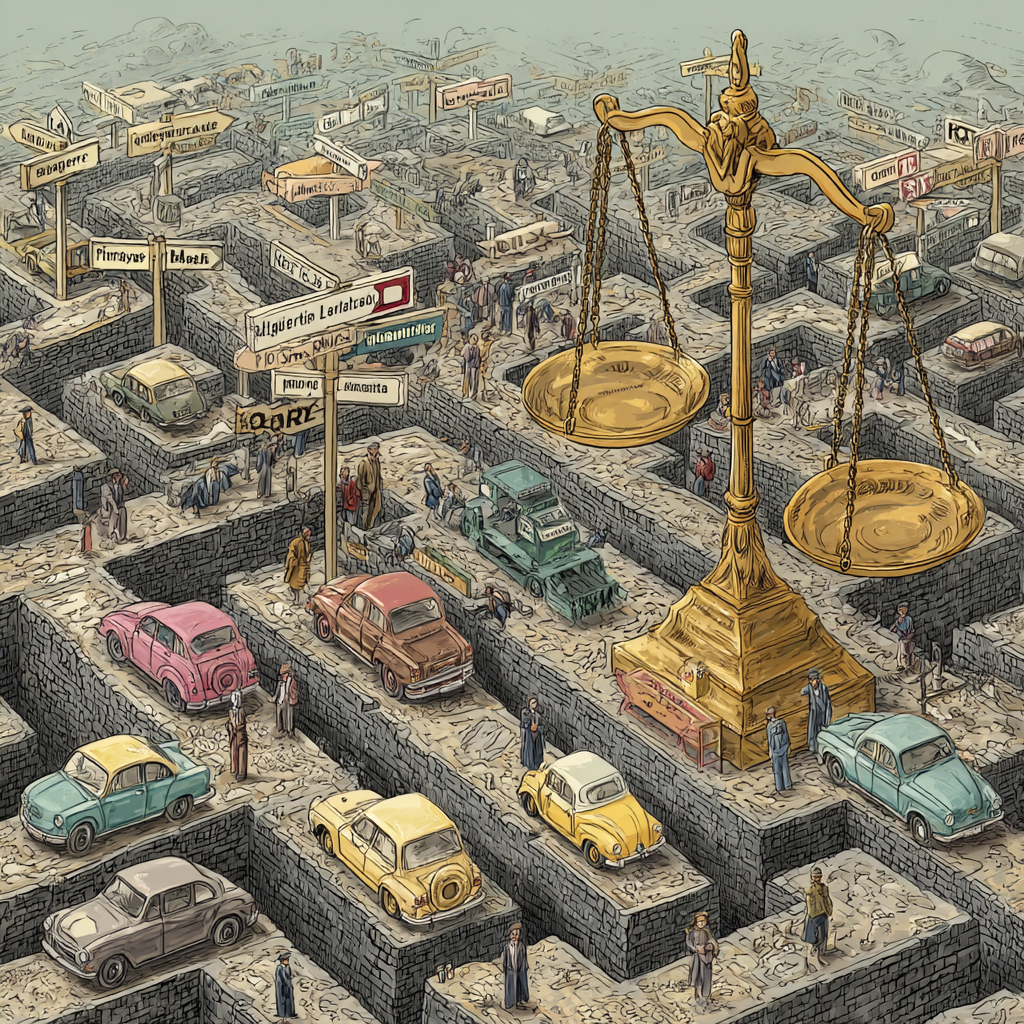

Introduction: Navigating the Complex World of Sex Offender Registration Laws

Navigating the maze of sex offender registration laws in the United States is no small feat. With 50 states and a patchwork of statutes, rules can change dramatically across borders. A persistent question—and the subject of many heated debates—centers on whether someone required to register as a sex offender in one state must also register if they move to another, especially when the new state’s law references “anyone required to register in another state.” Some theorists have even suggested that if a person isn’t required to register elsewhere, then they are automatically exempt in their new state.

This article breaks down that concept, explores the legislative intent behind these statutes, debunks common myths, and offers actionable legal perspectives—while also addressing the crucial role of constitutional principles like the Equal Protection Clause. You’ll learn:

- What state registration laws actually mean when referencing obligations from other states

- Why the so-called “loophole” theory fails both legally and practically

- The real motives behind these legislative provisions

- Alternative legal strategies for challenging unfavorable registration requirements

Whether you’re a legal professional, someone navigating the system, policy advocate, or simply interested in the nuances of interstate legal mechanics, this guide aims to clarify a notoriously confusing subject.

The “Looper” Theory: Does Out-of-State Registration (Or Lack Thereof) Dictate Local Obligations?

The Myth Explained

A commonly circulated theory holds that if a state’s sex offender registration law says you must register if you have a registration obligation in another state, then only people with such obligations are covered. Conversely, if you have no such obligation elsewhere, you’re off the hook. At first glance, this logic appears sound—interpreting statute language literally and narrowly.

Expert View: Why the Theory Falls Short

According to legal experts like Larry (cited in the original discussion), this theory, though appealing, simply doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. Why? Because:

- Statutes Must Be Read in Harmony: Legislatures design registration laws to cast a wide net, not to create avenues for “state shopping”—where individuals convicted of offenses in one state migrate to another in hopes of avoiding registration.

- Legislative Intent: The infamous “anyone required to register in another state” clause wasn’t meant as a loophole for escape; rather, it was included to close loopholes that would allow out-of-state offenders to slip through the cracks.

- Use of “Or” as a Conjunction: Statutes frequently include lists of covered offenses, both sexual and (in some cases) non-sexual acts with demonstrated sexual motivation, then tack on the “required elsewhere” clause. These clauses are joined by “or,” meaning any one criterion—local covered offense, out-of-state equivalent, or existing registration requirement elsewhere—triggers the obligation.

Example:

If Georgia registers for making obscene phone calls to a minor, but New Mexico doesn’t list that offense, the “required to register elsewhere” clause in another state could still force a Georgia transplant to register—even if that specific conduct wouldn’t register a New Mexico resident.

What About States Without the Clause?

In some states, the registration obligation hinges strictly on the local statute’s list of offenses or on offenses deemed “substantially similar.” Here, if your past conviction doesn’t appear on the list and there’s no “forced reciprocity,” you might avoid registration—unless the legislature has built in a clause to capture such out-of-state obligations.

Legislative Motivation: Closing Loopholes, Not Creating Them

State Shopping: Avoiding the Registry by Moving?

There’s a very real concern about “state shopping,” where individuals seek out states with less onerous registry requirements to shed their obligations. Recognizing that, many states amended their statutes over the years:

- Broadened Coverage: By adding “anyone required to register in another state,” they prevent offenders from side-stepping registration simply by crossing state lines.

- Uniform Public Safety Approach: Legislators prioritized consistent public safety standards over technicalities that could exempt otherwise eligible individuals.

Real-World Analogy:

Think of it like vehicle inspections. One state might not require emissions testing, but if you move to another that does—and your car fails—you can’t simply say, “but my old state didn’t care.” Similarly, registration laws adapt to where you reside, not where you came from.

How Courts Read and Apply These Laws

The Role of Conjunctions: “Or” vs. “And”

In statutory construction, conjunctions matter:

- “Or” makes any listed condition sufficient.

- “And” requires all conditions be met.

Most states link registration triggers with “or,” so any one qualifying factor initiates the requirement. This further undercuts the loophole theory.

Statutory Examples

- Arkansas: Lists covered offenses, adds “or” for out-of-state equivalents, then finally “anyone required to register in another state.”

- Georgia: Registers some unique offenses, like obscene phone calls to minors, which other states often do not.

- New Mexico: Sometimes requires “equivalent” or “substantially similar” offenses, which may narrow coverage compared to states using broader language.

The Faulty Loop Theory in Action: Practical Consequences

Suppose someone convicted in Georgia for an offense not covered on New Mexico’s registry moves there. If New Mexico’s law doesn’t have an “anyone required to register elsewhere” provision, the person likely avoids registration. But if another state uses the broad clause, they must register, regardless of local offense lists.

Key Insight:

These statutory provisions are designed to expand—never limit—the reach of registration obligations. Their purpose is to ensure public safety by including, not excluding, individuals who might otherwise slip through regulatory cracks.

Legal Strategy: The Real Argument—Equal Protection Clause

If you believe you’ve been unfairly singled out upon moving to a new state, the better argument isn’t the loophole theory, but a challenge based on constitutional guarantees such as the Equal Protection Clause.

Larry’s Perspective:

Instead of arguing technical statutory interpretation, argue that being treated differently than local residents violates Equal Protection. For example:

- If a Georgia transplant faces registration in New Mexico for obscene phone calls (not a listed offense for NM residents), they could challenge that as unconstitutional special treatment.

- Analogously, vehicle registration can’t single out newcomers. If New Mexico interpolated Georgia’s fees for out-of-staters, that would be discriminatory—and likely unenforceable.

Steps to Take When Challenging Registration Obligations

- Know the Law: Read the local statute closely—are obligations triggered by offense lists, “substantial similarity,” or “registration elsewhere”?

- Seek Legal Counsel: These issues can become highly technical and precedent-driven; knowledgeable attorneys can mount constitutional challenges where appropriate.

- File for Relief: Equal protection arguments must be raised in court, potentially all the way up to the state’s Supreme Court or even federal courts if necessary.

Frequently Asked Questions and Common Misconceptions

Can moving to a new state erase my registration requirement?

Not necessarily. States use a variety of mechanisms to keep registration obligations intact for newcomers, especially those “required to register in another state” clauses.

What if my offense isn’t listed in my new state?

Potentially, you could avoid registration—unless your new state’s law includes those broader reciprocity clauses.

Are constitutional challenges effective?

It depends on the specifics, such as disparate treatment compared to local residents. Courts sometimes uphold state schemes for public safety, but strong facts and good legal arguments can bolster Equal Protection claims.

Synthesis: Key Takeaways

Understanding the interplay of state registration laws is critical for anyone dealing with these systems. The idea that being unregistered elsewhere shields you upon interstate relocation is, in most cases, a myth. Statutes are carefully worded to prevent avoidance, using broad conjunctions and out-of-state clauses precisely to close loopholes—not to open them.

Remember:

– Statutory language is usually expansive, not restrictive.

– Legislative intent is to cover, not exclude, individuals with out-of-state registration obligations.

– The real path to relief lies in constitutional arguments, not technical interpretations.

Actionable Next Steps

- Research Your State’s Laws: Don’t rely on rumors—read the relevant statutes yourself or consult legal resources.

- Consult a Qualified Attorney: Particularly one experienced in registry law, to analyze your situation in depth.

- Stay Informed: Laws change frequently. Subscribe to legal updates or advocacy group newsletters in your jurisdiction.

Conclusion

Sex offender registration law is among the most challenging areas of American legal practice, especially as states try to harmonize public safety with constitutional rights. The so-called “loophole theory” doesn’t stand up to close scrutiny, but options remain for those seeking fair treatment—primarily through equal protection arguments and constitutional litigation. In a field where lives and liberties are at stake, knowledge, preparation, and the right legal strategy are your best shields against misinformation and overreach.

Leave a Comment